9th & 10th September, Westpoint Arena, Exeter. 100s of suppliers, seminars, expert advice. Explore all the options, all in one place – only at Build It Live.

Book your free tickets now

9th & 10th September, Westpoint Arena, Exeter. 100s of suppliers, seminars, expert advice. Explore all the options, all in one place – only at Build It Live.

Book your free tickets nowGround source heat pumps (GSHPs) take low-grade energy from the ground. They then convert it into usable energy at a higher temperature for space heating and water heating.

The easy way to understand it is that the pump works on the same principle as a refrigerator, but operating in reverse.

The sun heats the ground in the United Kingdom to an average temperature of approximately 12°C. In this sense, GSHPs are actually making use of solar energy and could be considered renewable. But it’s worth bearing in mind that they still require mains power to run the pump.

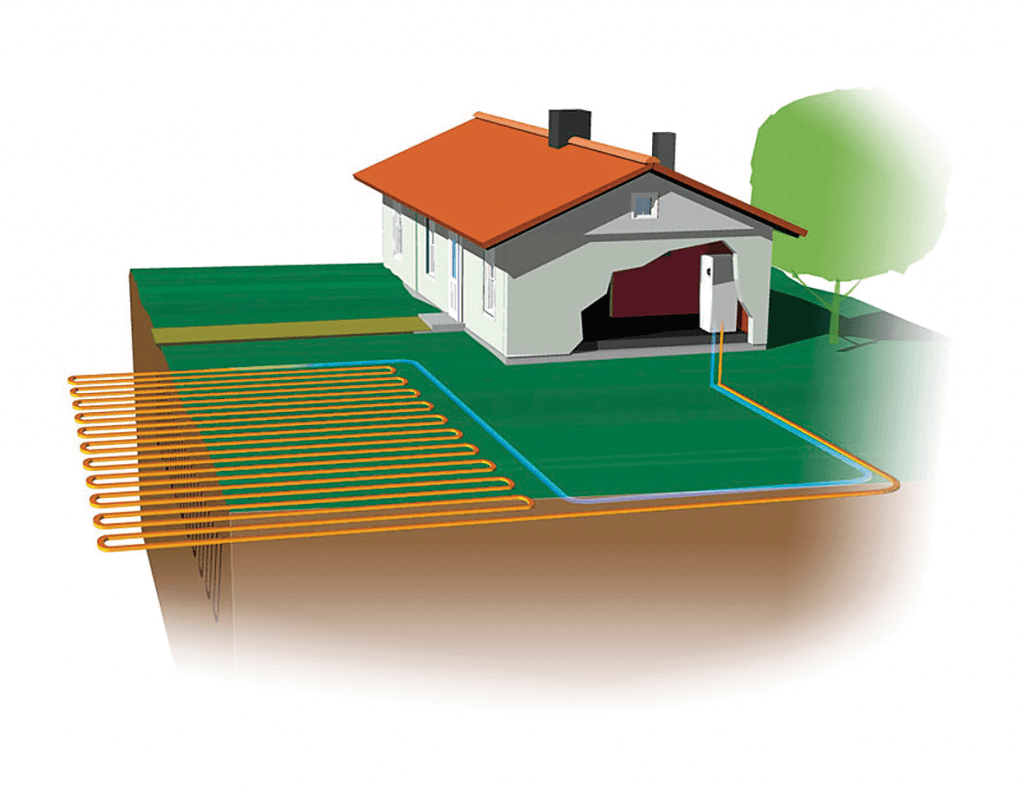

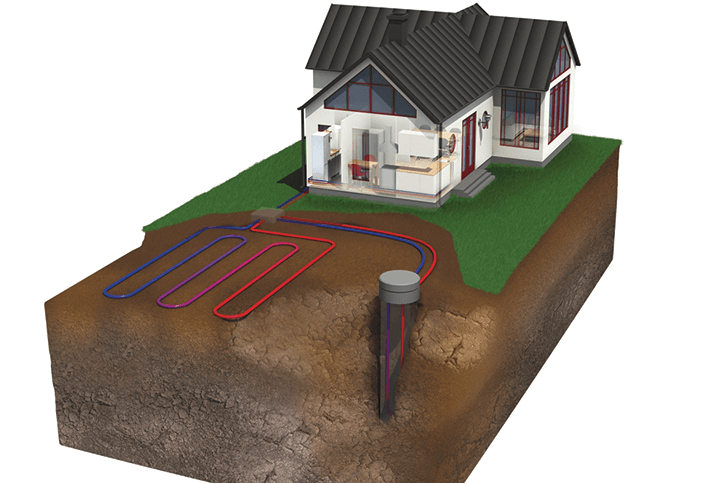

Most domestic installations use closed-loop systems.

This means that a system pumps the collector fluid (water and anti-freeze) through a sealed loop. The liquid then draws in warmth from the ground and returns at a higher temperature.

The heat pump compresses the collector fluid and subsequently the distribution system (typically underfloor heating) absorbs the heat. The system then reduces the pressure by expanding the fluid. This causes the fluid to cool down before it returns to the underground collector and the process starts again.

Where there is sufficient land available, you can use a horizontal collection loop, with pipes laid in trenches that lie approximately 1.5m below ground level. If space is tight, the alternative is to install a vertical solution, which generally reaches between 50m and 90m deep.

It’s worth bearing in mind that heat pumps can also supply cooling. Demand for this could become significant if climate change accelerates dramatically.

The installed performance of a GSHP is a huge factor in determining whether you can save money or carbon emissions when compared to alternative methods of heating your home.

While their source of warmth is solar energy in the ground, a GSHP is in reality an electrical form of heating, as it needs power to operate.

The core benefit lies in the fact that you get several units of heat output (measured in kilowatt-hours, kWh) for each unit of electrical input. The ratio between these gives you what’s known as the Coefficient of Performance (COP).

So, if a system runs at a CoP of three, this means it produces three units of heat energy for each unit of electricity.

Most new build projects include a plant room to host the technology that goes into a modern home – as with this ground source heat pump installation by Chelmer Heating Solutions

The Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) is another key figure to scrutinise. This sums up the ratio of total energy input to total heat output over an entire heating season. Research suggests an average SPF of three for ground source heat pumps (less if they supply domestic hot water as well as space heating, as the pump isn’t as efficient when raising water to higher temperatures).

But clearly some installations can achieve better results. The design of the collector loop, distribution system etc will have a big impact on the actual results you see – so ultimately

it’s the efficiency of the whole setup that really matters.

One criteria that’s often overlooked is an appliance’s lifespan. GSHPs contain very few moving parts, so should last for many years and require minimal maintenance.

Electricity costs about three times as much as gas per kWh. So if your installation achieves the average SPF of three, it will prove similar to gas boilers in terms of running costs.

Your bills should be lower than using oil or LPG, though, and much cheaper than electrical resistance heating.

If the SPF is above three, then it begins to be cheaper to run than natural gas – but bear in mind the installation price will be more than for an equivalent boiler.

The curveball here is the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). Funded through general taxation and overseen by Ofgem, this scheme is available to new entrants until 31st March 2021. The RHI provides a payment per kWh of heat generated by a qualifying installation ).

From April 2019, the tariff for GSHPs is 20.89p per kWh (compared to the cost of gas at around, say, 4p/kWh). They adjust the amount that you’re paid to take into account the electricity required to run the pump.

So, if your installation had an SPF of four, a quarter of the total heat would be subtracted. Thus your payment would be based on three-quarters of the heat demand declared on the EPC.For domestic projects, the amount of heat generated is usually deemed based on the estimated annual space heating needs stated on your property’s EPC (and hot water, too, if the pump provides this). So the amount of heat you actually use will make no difference to the payments you receive.

Payments are also capped. The annual limit is 30,000kWh for GSHPs (which is higher than for air source heat pumps or biomass). So at 20.89p/kWh, the maximum subsidy would be £6,267 per annum (before deductions for the electrical input).

Eco-Friendly Coastal Home in West SussexTenacious developer Rob Hall and his partner Cecilie Jacobsen had their hearts set on creating a three-storey family home in an idyllic coastal village in West Sussex. They wanted to make it as eco-friendly as possible, so they installed a ground source heat pump. Three 120m deep holes were drilled in the back garden for the system and two sturdy retaining walls were constructed deep inside the earth on either side of the plot, using 7m contiguous reinforced concrete piles. Learn more about the couple’s experience here |

Over seven years, this should offset the initial cost of installing a GSHP.

Bear in mind, though, that most new homes will be well insulated, so won’t have such a high heat demand.

So if running costs are critical to you, be sure understand the figures before making your decision.

Learn More: Ground Source Heat Pump FAQ

Fitting a GSHP requires substantial groundworks for the collector loop (with vertical boreholes more expensive than horizontal types).

Costs can range from £15,000 to £30,000 or more for a typical domestic installation. Prices depend on the size, the property’s heat demand, the type of collector, and how much of the distribution system is included.

But as we’ve seen, in the right circumstances this can be offset over several years of RHI payments.

If your heat pump is replacing a non-electrical heating fuel (like gas or oil) in a large building, the extra electricity demand to run the GSHP may require an upgrade of the local power distribution system.

This will add to the cost and overall environmental impact of the installation. That said, low upkeep can help to reduce ongoing impact.

Traditional Fuel Replaced |

Payback Period for GSHP with RHI |

Payback Period for GSHP without RHI |

Estimated Annual RHI Payments |

| Direct Electric Heating | 6-8 years | 12-18 years | £2,610-3,940 |

| New Oil Boilers | 12 years | 29 years | £2,610-3,940 |

| New Gas Boilers | 14 years | 47 years | £2,610-3,940 |

Source: Local Government Association (2016)

Ground source heat pumps are appropriate for new homes or existing homes with significant garden space.

That’s because they require either a substantial area of unshaded ground (approximately 10m of trench per 1kW of heat energy produced) or access for a drilling rig for vertical boreholes.

Ground conditions can also make a big difference to both cost and viability.

The technology works best when combined with an underfloor heating system (UFH) or oversized radiators. UFH runs at a lower water temperature than conventional radiator systems, so they require less energy to heat.

So if you’re not planning to upgrade emitters in an existing home, a GSHP probably won’t be appropriate.

The bottom line is you should work with a specialist to identify the right solution. Each situation is different. When looked at in the widest perspective, GSHPs are likely the most cost effective option when you are not using mains gas.

But in ultra low-energy homes where you don’t need much heat anyway, the fitting costs may lead you to an alternative.